Saskatchewan Rock Formations Reveal Past Life, Suggest Future

April 5th, 2022

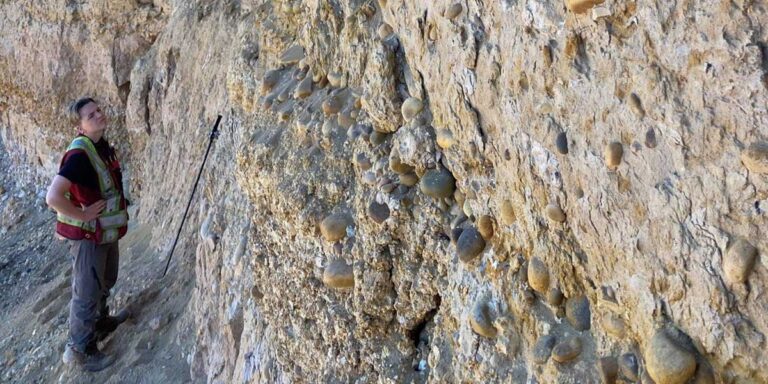

Meagan Gilbert measuring gravelly river deposits north of the town of Eastend that are characteristic of the lower Cypress Hills Formation. Photo by Amanda Thimpsen.

Meagan Gilbert measuring gravelly river deposits north of the town of Eastend that are characteristic of the lower Cypress Hills Formation. Photo by Amanda Thimpsen.

Meagan Gilbert’s interest in research was sparked when she recognized a gap in the data available from Saskatchewan compared to Alberta. Her work is helping people far beyond Saskatchewan understand how ancient life was impacted by climate change and what that could mean for our future.

Telling the story of ancient life in Saskatchewan and how those life forms were impacted by a changing climate is one that Meagan Gilbert, geologist-in-training, is uniquely qualified to tell.

It’s a story that is unending. While her research in the southwest corner of the province contributes to our understanding of past life, it is also providing insight into what could occur in the future.

Her study of geology is key to her telling that story. Outside of her work as a resident geologist for the Saskatchewan Geological Survey doing economic geology, she continues her research into the Cypress Hills Formation, which she explains has a rich story to tell.

“I’ve kind of made a niche for myself,” said Gilbert, who also serves as an adjunct professor at the University of Saskatchewan and teaches geology classes for Northland College.

“I look at the geology and then I look at the paleontology and I try to combine those things to come up with a more fulsome story of what was going on in some of these deposits, particularly throughout Saskatchewan.

“That’s where I’ve made my career out of it.”

Precambrian 2021: A photo of me teaching fieldschool in the Precambrian shield for the University of Saskatchewan in 2021. Photo by Amanda Thimpsen.

Precambrian 2021: A photo of me teaching fieldschool in the Precambrian shield for the University of Saskatchewan in 2021. Photo by Amanda Thimpsen.

Inspired by southwest Saskatchewan

In years past, those interested in that type of story about ancient life might have looked for it here in Canada by going farther west.

“There are a lot of people who just find it interesting that there’s this kind of stuff in Saskatchewan and that you can tell these kinds of stories with deposits in Saskatchewan,” said Gilbert.

“Everybody thinks of Alberta when you think of prehistoric life. Not a lot of people think of Saskatchewan.”

Growing up in the Eastend area, Gilbert had some early experience with what could be found in that southwest region of the province.

“It’s pretty famous for being basically like a mecca for geological and paleontological activity,” said Gilbert.

“I grew up on a cattle ranch and there was a lot of outcrop exposure of what I would later come to understand are Paleogene deposits of the Ravenscrag and Cypress Hills formations.

“So, I could actually go out in the hills and observe the geology and make observations that, I didn’t realize at the time, were scientific in nature and prospect for fossils.

“I had an inherent interest, but it was fostered by living somewhere you could actually explore that.”

Recognizing her potential

Going from being a kid interested in rocks and fossils to becoming a respected researcher in her field is a compelling story on its own.

“I actually never really had any interest in pursuing academics,” said Gilbert.

“I happened to get a job at the T.rex Discovery Center (in Eastend) and I was mentored by some people there as a high school student.

“Eventually, I met the right people at the right time who encouraged me to go to university after I had already been graduated for a little while.

“It seemed like the logical thing to go to the University of Saskatchewan because they had a very reputable geology and paleontology program.”

Learning of a gap in research

She began her studies by pursuing a degree in paleobiology, which required her to take a variety of classes, including that which would become her preferred area to study – even though her love of it grew over time.

“I actually thought geology was the least interesting discipline of all the disciplines I was studying,” said Gilbert.

“But as I advanced and took more classes, it became my favourite. You had to take biology, archeology, and geology to get this paleobiology degree, and (geology) became what I found most interesting.”

During her geological studies, she learned about deposits from the late Cretaceous period in southwestern Saskatchewan. The Cretaceous period was 145 million to 65 million years ago. During this time period, North America was bisected from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic by an interior seaway known to Earth scientists as the Western Interior Seaway. The western margin of Saskatchewan sat along this shoreline, so any fluctuations in sea level were recorded in the rocks deposited during this time. Any plants or animals living along this ancient shoreline would be affected by rapid changes in sea level.

Gilbert was intrigued that these late Cretaceous period deposits in southwest Saskatchewan are the same age as those at Dinosaur Provincial Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Alberta known for being where a number of high-quality dinosaur fossils were found in the Dinosaur Park Formation.

A small fragment of a left lower jaw from a small artiodactyl found at Anxiety Butte. An artiodactyl was from an even-toed hooved animal family that includes bison, deer, camels, and pigs. Photo by Meagan Gilbert.

A small fragment of a left lower jaw from a small artiodactyl found at Anxiety Butte. An artiodactyl was from an even-toed hooved animal family that includes bison, deer, camels, and pigs. Photo by Meagan Gilbert.

Seeking Saskatchewan data

Learning about the data from this area of Alberta, and recognizing the potential for that same type of data to be collected in Saskatchewan, gave Gilbert an idea for her future. She spoke with a couple of professors at the University of Saskatchewan who study sedimentology and stratigraphy and explained her interest. Sedimentology is the study of sediments and the processes that result in their accumulation and formation, both in the modern day and in the geologic past. Stratigraphy is the study of the layers that result from the accumulation of sediments, which can be used to tell geologic time, or understand past environments.

They agreed to take her on as a master’s student. She continued her course work to gain the knowledge and skill she needed to conduct the research, including learning more about the geology of Saskatchewan. During her studies, she was “finding gaps in the record and wanting to fill those gaps in myself.”

As she was studying southwest Saskatchewan’s geology for her master’s degree, she came across a significant amount of microvertebrate sites. As she explains, these are hydrologically-controlled sites where the remains of disassociated animals accumulate, such as teeth, small bones, and scales. Finding thousands of bits of these organisms in one place suggests they lived at the same time, in the same space and in the same ecosystem.

“You can’t truly understand the geology without understanding the paleontology and vice versa. So, I was like, ‘Maybe I should just expand this, do a PhD and study this particular rock unit in three dimensions’,” said Gilbert.

“So, studying the sedimentology and stratigraphy and how that relates to the depositional environments and paleontology, and how that relates to paleoecology and the paleoclimate.”

She included in her research trace fossil evidence as it is “such a great barometer for understanding climates and depositional environments and subtle changes you might not pick up from the sedimentology alone.” Depositional environments are, in Gilbert’s words, “an accumulation of sediment controlled by all factors that would affect a modern environment.” Whether it is the site of a lake, river or ocean, each of those environments have their own particular types of sediments and features that are reflected in the rock record.

“To understand depositional environments (is) to measure and map the rocks and tease out all the details and use that evidence to figure out what environment those sediments would best fit into.”

From her research, she was able to use these types of environments as “a proxy for what happens to coastal environments during relative rises in sea level and how that affects the organisms that are living along those coastlines and results in faunal turnovers over geologic time.”

Meagan Gilbert standing at the top of Anxiety Butte, which is about five kilometres north of the town of Eastend. She is at the top of the Cypress Hills Formation. Photo by Amanda Thimpsen

Meagan Gilbert standing at the top of Anxiety Butte, which is about five kilometres north of the town of Eastend. She is at the top of the Cypress Hills Formation. Photo by Amanda Thimpsen

In the field

Gilbert collected thousands of fossils during her research, contributing them to the collection of the Royal Saskatchewan Museum. To do this work, she would apply for permits, getting permission to access remote sites in the southwest part of the province.

Some geologists speak of the severe conditions they experience doing field work in the northern part of the province, but Gilbert said the conditions can also be harsh in the southwestern parts of Saskatchewan as well.

“You’re in a massive community pasture where literally nobody lives for hundreds of kilometres and you can’t drive on the grass there,” said Gilbert, who now lives in La Ronge.

“You have to walk into these sites, so, just the feat of getting to some of these sites was almost insurmountable.”

She would have to hike out to field sites with equipment to bulk sample for the tiny fossils these sites contained.

“There’s a reason people maybe avoided studying some of these things,” said Gilbert.

Tying the past to today

So, what do her findings about the late Cretaceous period, when Saskatchewan had a fluctuating sea, mean for understanding changes occurring in modern times?

Today, there is concern about the changes in sea level and what that means for the future of those living on the coastlines. But Gilbert says that when sea levels change, evidence from the past shows the scale of the impact on animal life is not what one might expect.

“Essentially what this study did determine is that there are changes in the fauna that live along these coastlines and it does affect them,” said Gilbert.

“But, at least at that point in time in the Late Cretaceous, it wasn’t affecting them to such a degree that it would have caused mass extinctions.

“You essentially end up with organisms shifting their patterns and shifting their environments and some might evolve or become extinct, but you don’t end up with these large-scale extinctions that you might expect there to be.”

Gilbert has since moved beyond that research to her current focus, which she says is even more relevant to modern times than what she learned studying the Dinosaur Park Formation. She is studying another time period – the Paleogene period which was from 66 million to 23 million years ago – with its own depositional environments by looking at another formation in Saskatchewan – the Cypress Hills Formation.

“I can’t overstate how important it is because there are very few deposits from the late Paleogene or the Paleogene in general throughout Canada,” said Gilbert.

“The Cypress Hills Formation has the only high-latitude non-Arctic fauna known from this time in North America.

The research I did in the Cretaceous (period) tells us about sea level change – and that’s important. “But the research that I’m doing in the Cypress Hills Formation actually tells us about major turnovers of entire groups of organisms.

“It’s capturing this very poignant time of major changes that is analogous with what we’re experiencing today with mammals.”

The Paleogene period followed the Cretaceous period. During the Paleogene period, the climate was changing significantly on a global scale with temperatures fluctuating by several degrees.

Earlier in that period, the area now known as southwest Saskatchewan was subtropical and forested, but as the climate cooled, grasslands appeared. Those grasslands are familiar to us in these modern times.

“All of that transition is recorded in the Cypress Hills Formation,” said Gilbert, who explained that particular formation spans about 28 million years.

“So, that is a really useful barometer for the things that we’re experiencing today and what we could be experiencing into the future,” said Gilbert.

What the past reveals

As the types of plants living in that area changed, so, too, did the types of animals. Gilbert explains that when the area was a patchy forest, the animals living there tended to be “really flat footed and have multiple toes.” There is evidence of those animals at the base of the Cypress Hills Formation, including the brontothere, which looked somewhat like a rhinoceros.

The depositional environments of the Cypress Hills Formation tell us that the environment was originally a patchy woodland but was evolving to be more like the Serengeti of Africa, with extreme seasonally wet and dry seasons. The animals living in what was becoming the plains of North America had to adapt to the evolving environments. When grasslands started to dominate the landscape, the animals living there evolved to be more like today’s horses, deer, bison and, even, camels.

“It’s more advantageous to reduce the number of toes and have longer legs for speed to evade predators who are more likely to see their prey in an open grasslands environment,” said Gilbert.

“The evolution of horses in the Cypress Hills Formation is a great example of that, who evolved from being the size of a medium-sized dog with three toes, to the long-legged, single-toed animals we know today that are built for speed.”

At the top of the Cypress Hills Formation, there is evidence of those animals there.

Explaining this transition in the types of animals living in that area over that period of time requires more than a single theory. But Gilbert explains that looking at individual types of animals from that time and place provides some insight.

Gilbert outlines a theory that explains the extinction of the bronothere. Their teeth were suitable for browsing shrub plants. As the climate changed, so, too, did the types of plants growing in that area. Grasslands appeared as the environment cooled. The soft enamel of the brontothere’s teeth was not equipped to handle eating grasses and their teeth wore down while they were still young, leading them to starve.

“Brontotheres are the most common fossil at the base of the Cypress Hills Formation, but by the top they are non-existent, and had gone completely extinct.”

Eventually, the ecological role brontotheres had, which was similar to the modern water buffalo in Africa, was

filled by bison and other grazing animals. Horses and bison evolved high crowned teeth that can withstand the wear and tear grazing grasses places on teeth. Brontotheres were not able to adapt so quickly.

“That’s a small example of some of these faunal turnovers that you can see,” said Gilbert.

“If climate change is significant enough to have a huge effect on a continent, or even globally, you will see entire groups of organisms go extinct. Some organisms can’t adapt fast enough to whatever pressure is being put on them due to the resulting environmental and ecological changes caused by climate change,” said Gilbert.

“So, a combination of environment and an organism’s ability to adapt dictates whether they can survive or not. As organisms disappear, other groups will rise up and take over those niches left vacant by those that went extinct.”

Sharing southwest Saskatchewan’s story

Gilbert spoke at the joint annual meeting of the Geological Association of Canada (GAC) and the Mineralogical Association of Canada (MAC) in November 2021 explaining this story contained within the rocks of southwest Saskatchewan.

“This research has been very, very well received by the paleontology and geological community,” said Gilbert, who has collaborated with some paleontologists/curators on this research – Emily Bamforth (on the Cretaceous period research) and Frank McDougall and John Storer (on the Cypress Hills Formation research.)

“Probably the biggest thing that I bring is a slant on the geology. So, you know, we talked a lot about the fauna, but that’s only a very small part of the puzzle that I work on.”

Gilbert’s interest in research was sparked when she recognized a gap in the data available from Saskatchewan compared to Alberta. However, this current research on the Cypress Hills Formation will go beyond what has been accomplished in Alberta.

It will help to tell a bigger story than simply classifying animals found in a formation from a specific time period. It will contribute to explaining those animals’ experiences living through changes to their ecosystems and environment due to climate change. That understanding of the past can help us understand how organisms could be affected by climate change going into the future.